Buckets & Dippers

by

John E. Valusek, Ph.D.

When I was a child, I spake as a child, I understood as a child, I thought as a child:

but when I became a man, I put away childish things.

-1 Corinthians 13:11

-1 Corinthians 13:11

The world of the child is largely created for him by the adults in his environment. He has little or no control over the kind of input he receives. His self-concept is therefore quite dependent upon how he is treated and what is said and done to him. This is appropriate and necessary for the child.

Sad to say, most of us, as adults, continue to function in much the same manner as when we were children. We continue to expect others to make us feel good and we blame them for making us feel bad. This is not only inappropriate for and adult but it is also quite unnecessary. While it appears to be true that most of us will always need and welcome support from those around us, it is not true that we are entirely dependent upon them. Yet, many of us never seem to discover this basic truth.

Because we apparently never eliminate many of our past learnings, even when harmed by them, it would be quite helpful if more people became aware of another way of thinking about the self that is, perhaps, a little easier to understand than some of the commonly accepted ways. A simple analogy is presented below which can be useful in helping to understand certain aspects of any personal relationship. However, it is particularly relevant when dealing with children or when observing many of the personal, emotional interchanges between and among children.

Let us imagine and conceive of the self as if it were a bucket. How we feel and how we will behave at any given moment is dependent upon how much or how little we have in our buckets. If our bucket is filled to overflowing, (which almost never happens), we will feel joy, have energy, and look forward to each day with enthusiasm. We will radiate warmth, be tolerant, forgiving, understanding and supporting of others. We will be glad we are alive and will exultantly proclaim, "Life is good." This is a well-developed pro-life viewpoint.

If our buckets are completely empty, (which almost never happens), we will feel and display all those characteristics which are opposite to those just stated. We will fell depressed, have little energy, and dread the coming of the next day. We will be unhappy, bitter, complaining, vindictive, and non-supporting of others. We will whine and miserably or angrily proclaim: "Life is lousy, purposeless, and hopeless." This is a well-developed anti-life viewpoint.

When faced with a person whose bucket is empty, most of us tend to become defensive---we feel threatened, fearful, hurt, or angry. It is likely that if we are strongly attacked verbally, we will respond in similar fashion. The emotional heat so generated is often not conducive to the development of healthy working relationships, not to the development of kindly feeling toward our attacker.

If we understood and applied the idea of the self as a bucket, we might discover that we would be able to behave quite differently than is usually expected. For example, when an attack is being directed toward us, rather than feeling hurt or counterattacking, we might find that we will be able calmly to view the upset person from a non-emotional vantage point. We could then say to ourselves: ‘Oh, you poor thing! You must have an empty bucket!" This places the attacker in an entirely different perspective. It can make us realize that his state of distress has very little to do with us, even though he seems to think it does. We will be able to realize that he is behaving that way because he feels so bad about himself. His bucket must be empty or else he wouldn’t be behaving that way. We might even be moved to feel genuine sympathy for him.

If we adopted the bucket view of self, we would understand that the motive underlying his attack is more directly attributable to his empty bucket than to anything we might have done to warrant criticism. We would realize that the person who is characteristically bitter is a person who has an empty or near-empty bucket. The bitterness is an expression of that emptiness.

The person with an empty bucket does not feel good about himself. He is actually upset with himself. In fact, he dislikes himself or else he wouldn’t be so consistently hateful toward others. This is axiomatic: anyone who consistently criticizes, finds fault with, demeans, ridicules, or maliciously gossips about another person actually dislikes himself. Furthermore, his behavior may be characterized as an attempt to engage in bucket dipping.

In addition to our buckets, each of us is equipped with a dipper. The consistently negative person keeps his dipper working overtime in a futile attempt to diminish another person and seemingly enhance himself. He may often succeed in the former, but he always fails miserably in the latter. It is impossible to fill one’s own bucket by dipping into another’s.

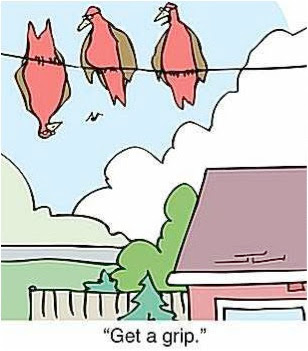

Knowing that each of us has a dipper as well as a bucket makes it possible to understand some otherwise fairly inexplicable behavior. It also becomes relatively easy to identify those who approach each day with dipper clutched firmly in hand, frantically engaged in attempting to empty the buckets of those around them. Finally, this view of behavior allows us to cast our own reactions in a different light.

The task then, for a concerned human being who is striving to become more pro-life and more positive, is to exercise every opportunity to help fill another’s bucket and to become intently alert to the spontaneously negative use of his own dipper.

How we go about attempting to fill buckets, to help another person feel better about himself, is actually already well known by most of us; although, we perhaps never realized quite how or why it was so significant. We fill others’ buckets by giving them sincere praise, compliments, accepting smiles, and displaying concerned interest. Strangely and inexplicably, we can add to our own buckets most directly and most mysteriously by working diligently to put drops into another person’s bucket. Under no circumstances do we ever add drops to our own by dipping into another bucket.

Children are relatively helpless. If more time and energy is spent dipping from their buckets than is spent putting drops into them, they have little recourse available to them other than to cringe in defeat or strike out in retaliation. Thus, the constant ever-present phenomenon of children tormenting one another (as well as aiming their dippers at adults), is a relentless quest to "get even." Of course they never succeed. But, their attempt can be understood as an unconscious understanding of at least one half of our concept of buckets and dippers . . . they realize that others have buckets which often contain considerably more than they, themselves, possess. They wrongfully believe that if they dip sufficiently deep enough and often enough, they will not only diminish the supply of the envied one, but will somehow add the stolen drops to their own impoverished supply. Their temporary smile of sadistic satisfaction is soon overcome by the stark reality of the barrenness of their internal environment and they repeat their foolish and harmful bucket-dipping behavior.

When you next look upon or have occasion to relate to a child who is angry, sullen, whining, belligerent, rebellious, obnoxious, cruel, tormenting, destructive or non-cooperative, know that you are witnessing the behavior of a person whose bucket is empty. Psychiatric, psychological, educational, or intuitive diagnosis is unlikely to add much to your knowledge about how to react or respond to him. If the diagnosis suggests a procedure or method of approach which is successfully employed and a positive change occurs in the child, you will know that his bucket must have been filled. Because his bucket was filled, he feels good about himself. When he comes to feel sufficiently good about himself, he will no longer need to respond as he did formerly.

The imperishable child within the adults you see all around you (as well as in your mirror), will respond likewise when his bucket contains a sufficient amount to tip the balance in favor of positive and pro-life attitudes.

-Gloria Pitzer

When you run into someone who is disagreeable to others, you may be sure he is uncomfortable with himself. The amount of pain we inflict upon others is directly proportional to the amount we feel within us!

Not Understood (by anonymous)

Not understood. We move along asunder,

Our paths grow wider as the seasons creep

Along the years; we marvel and we wonder

Why life is life, and then we fall asleep,

Not understood.

Not understood. We gather false impressions

And hug them closer as the years go by,

Till virtues often seem to us transgressions;

And thus men rise and fall and live and die,

Not understood.

Not understood. Poor souls with stunted vision

Oft measure giants by their narrow gauge.

The poisoned shafts of falsehood and derision

Are oft impelled ‘gainst those who mold the age,

Not understood.

Not understood. The secret springs of action,

Which lie beneath the surface and the show,

Are disregarded; with self-satisfaction

We judge our neighbors as they often go,

Not understood.

Not understood. How trifles often change us.

The thoughtless sentence or the fancied slight

Destroys long years of friendships, and estranges us,

And on our souls there falls a freezing blight:

Not understood.

Not understood. How many breasts are aching,

For lack of sympathy? Ah! Day to day,

How many cheerless, lonely hearts are breaking!

How many noble spirits pass away,

Not understood.

O God, that men would see a little clearer,

Or judge less harshly where they cannot see!

O God, that men would draw a little nearer

To one another! They’d be nearer to Thee

And understood.